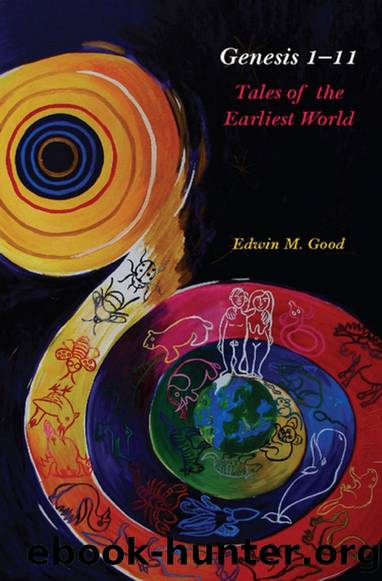

Genesis 1-11: Tales of the Earliest World by Edwin M. Good

Author:Edwin M. Good [Good, Edwin M.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780804779005

Google: CUokDwAAQBAJ

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 12787560

Published: 0101-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

Adam

Shet

âEnÅsh

Qayin

QÄnan

ChanÅkh

Mahalalâel

âÃrad

Yered

MehÅ«yaâel

ChanÅkh

MetÅ«shaâel

Metūshelach

Lemekh

Lemekh

Yabal, YÅ«bal, TÅ«bal-Qayin NÅach

The first three in chapter 5 are also named at the end of chapter 4.

But in chapter 5, QÄnan is surely a variant of Qayin, Mahalalâel of MehÅ«yaâel, Yered of âÃrad, MetÅ«shelach of MetÅ«shaâel. Lemekh is the same in both. Might the tradition have wanted somehow to separate Adam from responsibility for Qayin? It could not very wel have done

s o m e m o r e d e s c e n d a n t s 64

so, given the detailed story in chapter 4, and the storytel ers ended up being true to both sides of the tradition. There are differences of order, such as the fact that in chapter 4, âÃrad is the son of ChanÅkh, but in chapter 5, ChanÅkh is the son of Yered. These are just the sorts of differences we might expect if the genealogies had been passed down among different groups as oral tradition for centuries. Notice, too, that the whole group in chapter 4 are descendants of Qayin, and that list ends with Lemekhâs boast about Qayinâs being avenged, whereas in chapter 5

their counterparts are immediate descendants of Adam. That too might explain the differences. Someone might not have wanted the names to be exactly alike, and a few similarities would not be worrisome. I incline to think that the two lists came down by memory through different channels, and the people responsible for putting them next to each other didnât want to omit anything that might be true. This kind of lore, the sort that is expected to be memorized by people who care about it, tends to be quite stable, perhaps unlike the stories, which might have been known in general terms by the storytel ers, who probably would have done some improvising of language and event as they told the tales to audiences. And audiences might have been familiar with tales in general, knowing the episodes that were to be expected but not necessarily the very words in which they would be told.

Then there is the somewhat mysterious remark about ChanÅkh, who walked with Elohîm. The second time that is said, the text has a definite article with the word Elohîm: âChanÅkh walked with the Elohîm.â I had reason to note with chapter 1 that this term for the deity is plural in form. Why the definite article is here is uncertain, though it might suggest that he walked with multiple Elohîm. What the walking means is also debatable; it may imply both a close friendship and something of a nomadic life. ChanÅkh lives the shortest life of al of these folks, a âmereâ 365 years. But suddenly, after 365 years, he disappears.

There is no language about a death. âHe wasnât thereâ or, perhaps, translating more literal y, âThere was none of him,â âbecause Elohîm took him.â Took him how and where? We donât know. It is most unusual in this book. Not everyone in the Bible is a symbol or example of some-

s o m e m o r e d e s c e n d a n t s 6 5

thing, and ChanÅkh is like that.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(1038)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(969)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(964)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(957)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(874)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(790)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(766)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(762)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(758)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(721)

World Philology by(702)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(696)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(691)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(689)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(680)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(675)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(665)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(632)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(629)